by Tyron Devotta

As a writer, I was born into a world of objectivity, the one who was chasing that holy grail of writing without bias. My first job was in the Sun Newspapers (just to clarify, we did not have a page 3 nude) and it was those heady days for us, believing that we had the license to expose the truth. To us reporters it was power, but always tempered with the advice from our wise editor. Back then, we trusted a simple formula: stay detached, verify everything, and cross-check the story with three independent sources. If you did that, you believed you had done your duty — and that the truth, in its purest form, would rise to the surface.

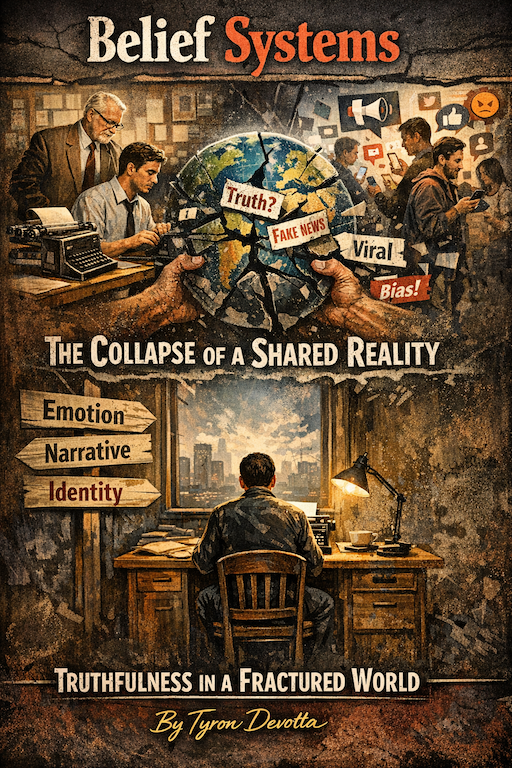

Belief Systems

This was probably true in a world that did not have social media. This phenomenon has changed the game, particularly the speed at which News can be delivered without any filters. Making it one of the most important factors in modern day information distribution. But today we know that if a story is echoed through social media for a million times it does not make it true. Just believable.

Stories today are written for belief systems, not in this quest for what we thought was the truth in the 70s and 80s. So in today’s world if the quest for truth is not our priority, so, what is it?

That question is no longer philosophical. It is operational. It sits at the heart of every newsroom or influencer’s agenda, every timeline, every breaking-news alert, and every “exclusive” that spreads faster than its own facts can catch up. We are living through the collapse of a shared reality (the mass mind), and what has replaced it is not ignorance, but something far more sophisticated: a marketplace of competing narratives at a micro-level, each armed with their own witnesses, their own video reel, and their own moral certainty.

Monopoly

Truth still exists, of course. But it has lost its monopoly. The age we now inhabit is not one where truth disappeared. It is one where truth has been demoted, nudged aside by more profitable, more emotionally satisfying priorities.

The first is attention. The digital world does not reward accuracy; it rewards interruption and the outcome is disruption. In the old model, the race was to confirm. Today, the race is to publish. Whoever speaks first owns the momentum, and momentum is everything. A story’s success is no longer measured by its reliability but by its reach. And reach is not earned only by truth! It is earned by friction. Outrage travels faster than context. Fear travels faster than explanation. Certainty travels faster than humility. In the current economy of information, nuance is a luxury item, and it rarely goes viral.

Control

The second priority is narrative control. In the 70s and 80s, much of journalism, at least in its ideal form, was about establishing what happened. Today the battle is not merely over events, but over meaning. Not “what occurred,” but “what it proves.” Not “who said what,” but “which side it benefits.” We no longer consume stories only as information; we consume them to find meaning in our belief systems. Every video becomes evidence. Every correction becomes an act of betrayal. Facts, once the foundation, are now treated like props, pulled in selectively to decorate a conclusion that was already emotionally decided.

Identity

And that leads to the third priority: identity. Social media has not simply turned us into publishers; it has turned us into tribes. People don’t only share what they believe, they share what they belong to. A story now functions like a badge: it signals loyalty, it signals worldview, it signals membership. That is why the most “believable” stories are not necessarily the most factual ones, but the ones that feel aligned with the reader’s existing moral map. If a story confirms what you already fear, it becomes “obvious.” If it supports what you already suspect, it becomes “proof.” If it flatters your side, it becomes “truth.” And if it challenges you, it becomes “fake.”

This is why the modern crisis is not simply misinformation. It is the deeper collapse of knowledge, the collapse of how we decide what is real. In that collapse, repetition becomes evidence, popularity becomes credibility, and volume becomes authority. The story that dominates does not always dominate because it is accurate, but because it is emotionally functional. It gives people a villain. It gives them a cause. It gives them the delicious comfort of certainty.

Emotion

There is also a quieter truth we are reluctant to admit: many stories today are not written to inform. They are written to regulate emotion. To soothe anxiety. To inflame anger. To produce catharsis. To offer vindication. That is why corrections rarely work. Because the story was never about truth in the first place. It was about tribal vindication!

The result is a world where belief is not a conclusion, it is a starting point. Facts are no longer what we use to arrive at meaning. Meaning is what we use to select facts.

And so we must ask: what becomes of the writer in this new landscape?

Detached

The old model taught us to be detached, to stand outside the story like a surveyor measuring truth. But today detachment is misunderstood. It is read as arrogance, or worse, as complicity. If you do not declare your allegiance, you are treated as suspicious. If you refuse to show outrage, you are accused of indifference. If you insist on complexity, you are told you are “both-siding.” The modern crowd does not want a writer who investigates; it wants a writer who confirms. It does not want a lens, it wants a mirror.

Yet this is exactly why the old writer’s role has never been more important.

Because the only antidote to a world drowning in belief is not a louder belief. It is a renewed discipline: not the illusion of perfect objectivity, but the deeper practice of truthfulness. Truthfulness is not the claim that you are neutral; it is the decision that you will be honest about what you know, what you don’t, what you can verify, what you cannot, and what you refuse to assume simply because it is fashionable to assume it.

Viritas

Truthfulness also means acknowledging that every writer stands somewhere. We have histories, fears, loyalties, blind spots. The difference is not whether bias exists, the difference is whether we interrogate it. In an age that rewards performance, truthfulness becomes a kind of rebellion. It becomes the refusal to write for applause. The refusal to write for a tribe. The refusal to trade complexity for virality.

So perhaps the question is not whether truth is still possible. Perhaps the real question is whether we still have the courage to pursue it when it no longer pays.

Because in this age, truth will not always be the most shared version of events. It will not always be the most profitable version. It will not always be the most comforting version. But it will remain the only version that can hold a society together without tearing it into factions of competing realities.

Civic Duty

In the end, the old writer is someone who protects the fragile infrastructure of shared meaning. In a world intoxicated by certainty, the writer’s job is to reintroduce humility. In a world addicted to speed, the writer’s job is to slow the story down. In a world that confuses noise with knowledge, the writer’s job is to insist that truth is not what travels fastest. but what survives scrutiny.

Truth may no longer be fashionable. But it is still necessary. And perhaps that is the final point: in the modern world, good writing is no longer only craft. It is civic duty.

First Article - Part 1 - The Human Guardians of the Narrative in an AI age

Second Article - Part 2 - Journalism in Crisis