By Tyron Devotta

At a recent session of the Collective for Historical Dialogue and Memory, historian Lara Wijesuriya delivered a compelling presentation that unpacked how Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka) was portrayed by British colonial authorities during World War II, especially after the pivotal fall of Singapore in 1942. Her presentation, titled “Ceylon and Propaganda during the Second World War”, explored the complex and sometimes contradictory layers of wartime imperial messaging, particularly how Ceylon was imagined and instrumentalized—as a colony, as a gendered space, and as a nascent national identity.

Collective for Historical Dialogue and Memory at Elibank Road, Colombo 05

Sriyan framed her analysis through three lenses:

- The imperial-colonial relationship,

- The household and domestic sphere, and

- The emerging national consciousness.

The Empire in Crisis: From Command to Partnership

Before the fall of Singapore, British wartime propaganda was confident, even paternalistic. The empire, led by the Crown, expected loyalty and labor from its subjects—especially its Asian colonies. Ceylon was depicted as a loyal supplier: of rubber, tea, coconut oil, and people. Propaganda urged the people of Ceylon to contribute more to the total war effort, presenting this as a noble duty to the “Mother Empire”.

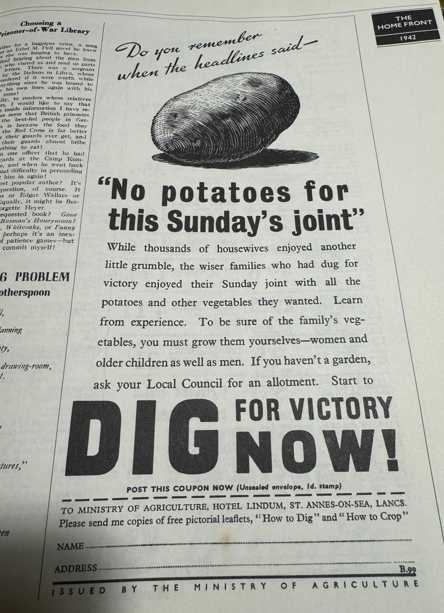

'Dig for Victory' - The Home Front 1942

But after Singapore fell in February 1942—a crushing blow that exposed the vulnerability of the British military in Asia—the tone of propaganda shifted. British officials, feeling betrayed by what they claimed was the “passivity” of local populations in Malaya and Singapore, began to see the cracks in their imperial armor.

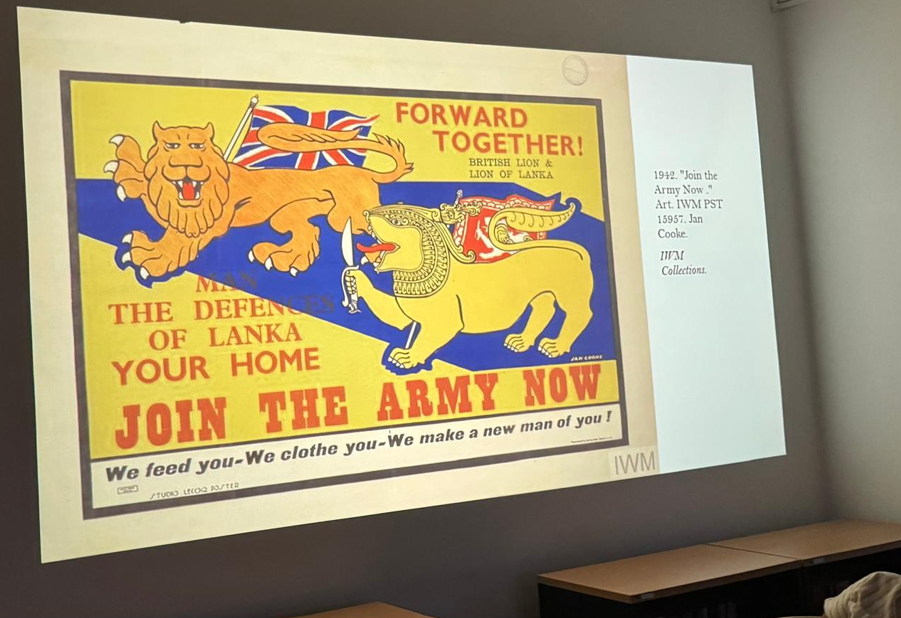

Suddenly, Ceylon was no longer just a compliant colony; it was a partner in survival. Propaganda began using language that emphasized shared destiny and mutual defense. Ceylon’s people were now depicted as stakeholders in the war, not merely subjects. This shift marked a significant moment in colonial messaging: the Empire was no longer all-powerful—it needed its colonies, and it had to ask for their help.

The Gendered Homefront: Mobilizing the Household

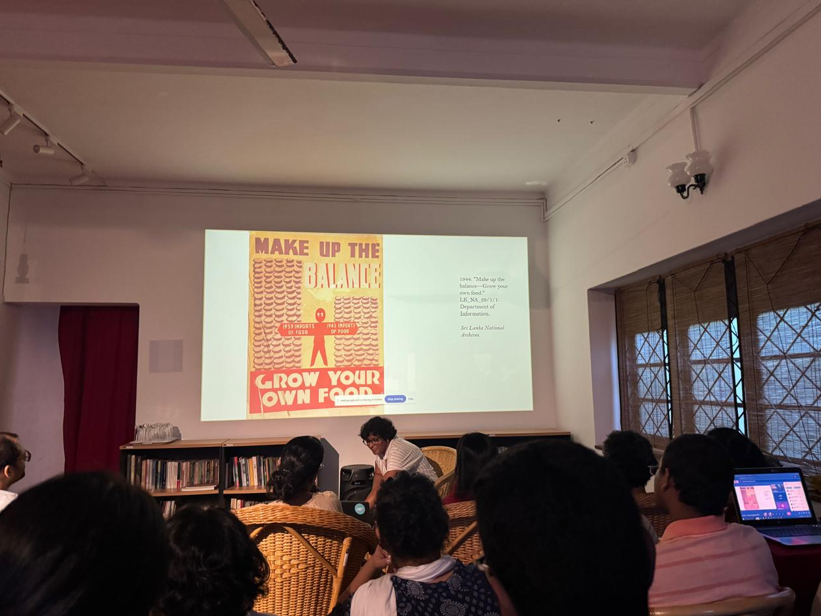

One of the most important aspects of Lara’s presentation was her examination of how wartime messaging targeted the household, particularly women. With rice imports from Burma cut off after the Japanese occupation, Ceylon plunged into food shortages. The colonial state responded by launching campaigns urging citizens to grow their own food and modify their consumption habits.

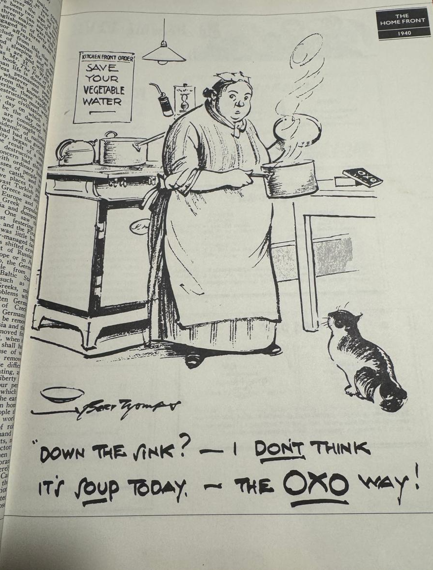

Posters, pamphlets, and radio broadcasts instructed women how to stretch rations, use substitutes (like rice flour for wheat), and maintain morale. The housewife was transformed from a private actor into a public economic agent, a domestic warrior in the Empire’s battle for survival. The propaganda often feminized the nation, casting Ceylon as a nurturing mother, and the household as a microcosm of empire, responsible for feeding not just their own families, but the broader imperial body. (Author's note: however this was not far from what was happening in Britain at that time, housewives were told to grow their own potatoes and save their vegetable water to make soup the OXO way!)

'The OXO Way!' - The Home Front 1940

Lara Wijesuriya, the historian, says this gendered framing did more than encourage thrift—it reinforced a moral economy where emotional labor, sacrifice, and quiet patriotism were expected from women. And through this, the domestic space became deeply politicized.

The National Idea: Ceylon as a Distinct Identity

Perhaps the most subversive effect of wartime propaganda was the unintended rise of national consciousness. In trying to persuade Ceylonese subjects to feel invested in the Empire’s survival, the British state began speaking of Ceylon as a distinct entity, capable of action, duty, and agency.

This rhetorical shift—necessary to win hearts and minds—unwittingly fostered the idea that Ceylon was not merely a province of Empire, but something separate, with its own role to play in history. The seeds of nationalism, planted in the cracks of colonial control, found fertile soil in this period.

This sentiment was sharpened by rising censorship, racialized divisions in the military, and suspicions of Ceylonese support for the Japanese. Posters warning of “careless talk” and rumors being tantamount to treason further reflected British anxiety. Stories circulated about scorched-earth policies and threats to burn crops—true or not, these only deepened distrust between rulers and ruled.

Conclusion: Between Loyalty and Autonomy

What emerges from Lara’s presentation is a nuanced portrait of wartime Ceylon—not as a passive pawn in a global conflict, but as a site of contested meanings, emotional appeals, and shifting power dynamics.

Colonial propaganda sought to mobilize labor, loyalty, and love for the Empire. But in doing so, it revealed the Empire’s fragility—and exposed the possibility of a future beyond it. In trying to shore up its dominion, the British inadvertently helped Ceylon imagine itself as something other than a colony.

From the rubber estates to the rice kitchens, from royal broadcasts to ration cards, World War II reshaped how Ceylon saw itself—and how it would soon chart its path toward independence.