“To introduce deep, rooted digitalization in a country, there has to be an attitude change. Digitalization is inherently anti-hierarchical—it thrives from the bottom up.”

India’s Digital Rise in a Deeply Hierarchical Society

This idea, though simple in phrasing, carries profound implications. Digitalization, at its core, seeks to democratize access to information, services, and opportunities. It promises to flatten the structures of power and bypass gatekeepers. And yet, one of the most successful digital transformation stories in the world today has unfolded not in a classless utopia, but in one of the most hierarchical societies on Earth—India.

India’s social fabric remains deeply stratified. Caste continues to define interactions in homes, villages, workplaces, and even within digital spaces. Class divides are growing, gender inequities persist, and linguistic and religious distinctions influence everything from employment to education. How, then, has India managed to build some of the most robust and inclusive digital public infrastructure on the planet?

This paradox is worth examining, not only because it defies conventional wisdom, but because it holds lessons for many other countries—especially in the Global South—seeking to build inclusive digital societies.

India’s digital transformation has not emerged from Silicon Valley-style start-up disruption. It has been state-led, deliberate, and rooted in the idea of digital infrastructure as a public good. Platforms such as Aadhaar, India’s biometric ID system, have registered over 1.3 billion people. The Unified Payments Interface (UPI) has revolutionized the way Indians transfer money, even in the smallest towns and rural corners. DigiLocker and CoWIN (used for vaccine registration during the COVID-19 pandemic) have similarly expanded the digital state’s reach into the daily lives of ordinary citizens.

When Top-Down Tools Fuel Bottom-Up Change

This infrastructure is not just top-down—it is interoperable, open-access, and designed to include those previously excluded. Millions of Indians, from urban gig workers to rural subsistence farmers, have been brought into the digital fold. In many ways, the Indian state has succeeded in simulating a bottom-up transformation through top-down tools.

Much of this success has been made possible by the mobile revolution. India today has over 700 million internet users, driven by widespread smartphone adoption and some of the lowest data costs in the world. The rapid spread of connectivity has enabled even the most marginalized to access digital services—from government subsidies to education, banking to telemedicine. With a mobile phone and internet connection, a migrant worker can send money to family, apply for a government scheme, or access health information—services that previously involved standing in line, paying bribes, or relying on a local bureaucrat.

Crucially, digital systems have enabled the bypassing of traditional gatekeepers. Farmers can access real-time market prices and sell produce directly. Women receive welfare payments into their bank accounts without male intermediaries. Citizens book appointments, file complaints, and verify documents online, often eliminating the need to interact with local power structures that once acted as filters—or obstacles—to access.

India’s Digital Paradox: Inclusion Amid Inequality

India’s political leadership also deserves recognition for its commitment to digital inclusion. Initiatives such as Jan Dhan (bank accounts for all), Aadhaar (digital identity), and mobile access—collectively known as the JAM trinity—have enabled financial inclusion and welfare delivery on an unprecedented scale. The focus was not merely on connectivity, but on inclusion: ensuring that every Indian, regardless of geography or social status, had a pathway into the digital economy.

And yet, for all this success, India’s digitalization has not eliminated hierarchy—it has merely routed around it. A Dalit woman may now hold a smartphone, access an Aadhaar-linked bank account, and receive government subsidies directly. But she may still face discrimination, harassment, or even violence in her offline world. Social power does not vanish when access is granted. Caste-based exclusion, gender bias, and digital illiteracy still shape the outcomes of digital interaction. And as platforms evolve, the digital world can reproduce the very inequalities it was meant to disrupt.

Access, in short, is not the same as empowerment.

Lessons from India’s Digital Transformation

India’s story holds lessons for other societies contemplating digital transformation. It shows that it is indeed possible to build powerful, scalable, inclusive digital systems in a society where hierarchy is deeply entrenched. But it also cautions us not to conflate digital reach with social reform. True digitalization—the kind that transforms not only services but also relationships and agency—requires more than infrastructure. It demands a shift in mindset: from control to trust, from privilege to inclusion, from hierarchy to equity.

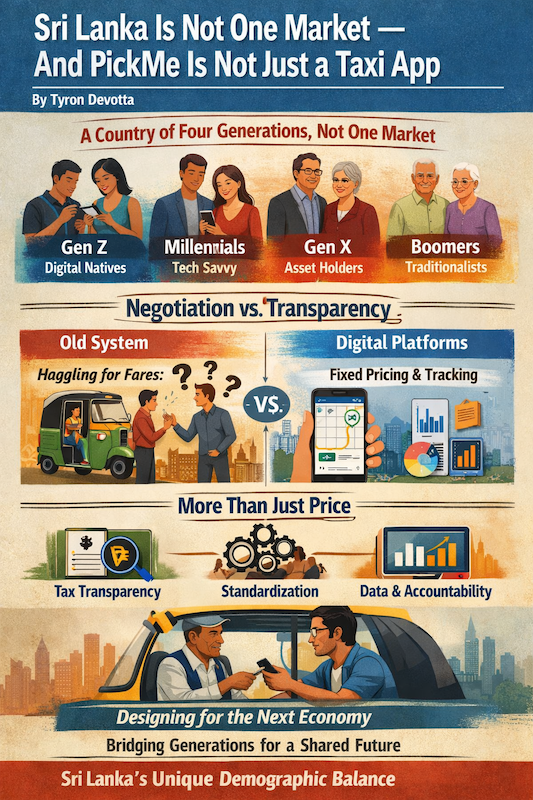

Countries such as Sri Lanka may be tempted to emulate India’s technological model, and rightly so. But they must also recognize that technology, while powerful, is not a magic wand. Without investment in digital literacy, data rights, and social safeguards, digitalization can easily deepen existing divides.

India’s paradox should not deter us—but it should deepen our thinking. Digitalization is not merely a technological project. It is a social one. And like any true transformation, it must begin at the roots.