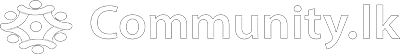

When we talk about caste and colorism in South Asia, the conversation often turns to India. Yet Sri Lanka’s own story — though different in origin — was profoundly shaped by the same colonial racial theories that hardened social hierarchies and redefined beauty standards.

Before the Colonizers: A Different Caste Order

Sri Lanka’s caste system was never a mirror of India’s varna-based order. Among the Sinhalese, Govigama farmers stood at the top, with castes like Karava (seafarers), Salagama (cinnamon peelers), and Durava (toddy tappers) below them. Among Tamils, Vellalars dominated landholding, with other groups tied to service and ritual. This was a system built on land, occupation, and local ritual duty — less rigid, and not directly tied to skin color.

Colonial rule transformed these fluid structures.

- The Portuguese began favoring certain castes for military and administrative roles.

- The Dutch went further, locking cinnamon-peeling castes into hereditary service for the VOC.

- The British institutionalized caste through the census, beginning in 1871. What had been a local social framework was now a rigid administrative category. Occupation, mobility, and identity were frozen in official ink.

The British Racial Lens

The real transformation came with the British racial imagination. Obsessed with hierarchy, they saw caste through the prism of “race.” Ethnographers like H.H. Risley in India argued that caste correlated with skin color — upper castes being lighter, lower castes darker. In Ceylon, this was mapped onto the Sinhalese–Tamil divide. The British eagerly promoted the idea that the Sinhalese were “Aryan” (lighter, purer, superior) while the Tamils were “Dravidian” (darker, inferior).

This was not science. It was colonial ideology, used to divide, to rule, and to justify European superiority. Yet its influence seeped deep into the local imagination.

Before colonialism, caste mattered more than complexion in marriage. Under the British, however, whiteness became prestige. To be fair-skinned was to be closer to the rulers, to “modernity,” to power. Marriage alliances began to prize fairness alongside caste status. Even today, Sri Lankan matrimonial ads ask for a “fair bride” or “fair groom,” a direct echo of colonial-era racial coding.

The British also left behind a cultural obsession with fair skin that reshaped ideas of beauty.

- Skin-lightening creams flooded the market, with “Fair & Lovely” becoming a household name.

- Beauty pageants like Miss Ceylon prized Eurocentric looks.

- Sinhala and Tamil cinema cast lighter-skinned actors as heroes and heroines, while darker actors were typecast as villains, servants, or villagers.

These stereotypes — colonial at their core — continue to dominate media and advertising.

The Legacy We Live With

Independence abolished caste restrictions in law and education. But socially, caste networks persisted — and colorism thrived. Today, in workplaces, on screens, and in families, lighter skin is still often read as more beautiful, more prestigious, more “modern.” This is not an ancient Sri Lankan tradition. It is a colonial inheritance.

If Sri Lanka is to break from this past, we must first recognize it. The idea that lighter skin is more desirable did not come from our soil; it was planted and nurtured by colonizers who used race to divide and rule. By understanding this history, we can begin to unlearn it — in our marriages, our media, and our mirrors.