by Tyron Devotta

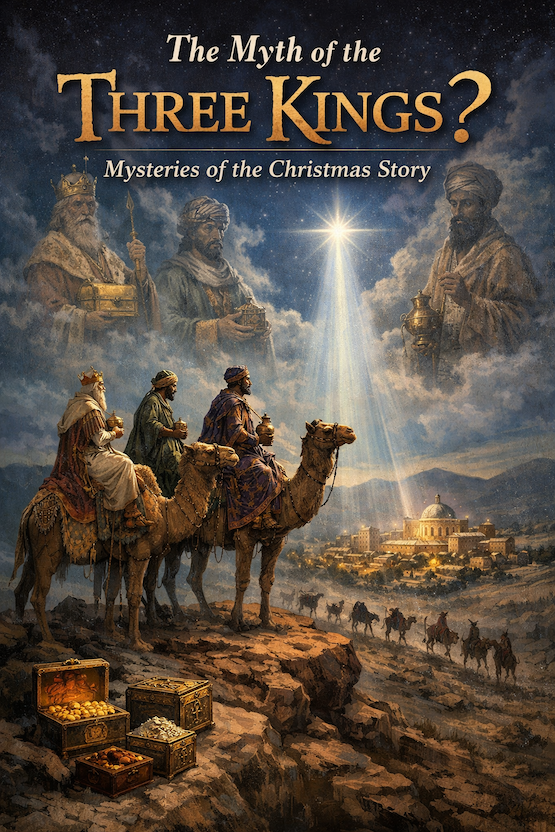

Every December, nativity scenes across the world repeat a familiar story: a baby in a manger, shepherds at one side, and three crowned kings bearing gifts at the other. In this scene the kings are so deeply embedded in Christian beliefs that few pause to ask a simple question: does the Bible actually say this?

Only one of the four Gospels mentions these visitors at all: the Gospel of Matthew. Matthew describes Magi from the East—a term that refers not to royalty, but to learned astrologers or priest-scholars. He does not tell us how many there were. He does not call them kings. He does not place them at the manger. And crucially, he never romanticises them.

They follow a star, consult a paranoid ruler, present gifts, and quietly disappear from the narrative. That is all. Everything else—the crowns, camels, royal robes, even the number three—comes from somewhere else.

How Three Became the Magic Number

The leap from Magi to three Magi was almost inevitable. Matthew lists three gifts: gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Early Christian interpreters assumed one giver per gift. Over time, a symbolic inference hardened into an accepted “fact.”

Why Scholars Turned Them into Kings

The bigger transformation was not numerical—it was political.

Early Christians, reading Matthew through the lens of the Hebrew Scriptures, connected the Magi to verses such as:

- Book of Isaiah 60:3: “Nations shall come to your light, and kings to the brightness of your dawn.”

- Psalm 72 10–11: “The kings of Tarshish and of distant shores will bring tribute…”

These passages were not written about the Magi. But they sounded like them. And so the Magi were retrofitted into prophecy as kings bringing homage to Christ.

This expedient move served a powerful theological message for the times: Jesus is not merely a local Jewish messiah, but a universal king recognised by the nations. But there was a cost in turning foreign scholars into exotic monarchs.

Matthew’s narrative is deliberately unsettling. Herod, an actual king, responds to Jesus with fear and violence. The Magi, foreign outsiders, respond with curiosity and reverence. When the Magi are turned into kings, that edge is dulled. The story becomes pageantry rather than critique. It stops asking hard questions about power, knowledge, and moral courage..

By the sixth century, Western Christianity had completed the transformation. The Magi acquired names—Caspar, Melchior, and Balthazar—and were recast as representing Europe, Asia, and Africa. This was not historical fact; it was storytelling.

The Kings Become real

By the Middle Ages, the Three Kings were no longer an interpretation. They were canonised by art, liturgy, and carols and a special feast day is dedicated to them.

We live in an age that prides itself on analysis. Sacred texts are scrutinised with the same tools we use to examine politics, media, and history. Nothing is exempt from questioning—and rightly so. Yet when it comes to ancient religious narratives, modern readers often fall into two choices: either accept them literally or dismiss them entirely.

The story of the Magi invites a more mature response.

A modern reader must first distinguish between text and tradition. The Gospel of Matthew speaks briefly of Magi from the East—nothing more. Over centuries, Christian tradition added numbers, crowns, names, and pageantry. This evolution does not invalidate the story; it reveals how communities shape meaning across time. Read carefully, the Magi are not decorative figures but a pointed narrative device. Matthew sets up a deliberate contrast: political power and religious authority are housed in Jerusalem, yet insight comes from outside. A frightened ruler clings to control while foreign scholars follow signs and act with moral independence.

The Kings in our times

For a modern audience, this tension is strikingly familiar. Institutions still resist uncomfortable truths. Outsiders and independent thinkers still recognise them first.

Modernity often assumes that symbolic stories are intellectually inferior to factual ones. This is a mistake. Ancient societies used symbolism to communicate truths about power, ethics, and human behaviour. The Magi do not need to be kings for the story to matter. At the same time, intellectual honesty demands that we acknowledge myth-making. Religious traditions grow, accumulate layers, and sometimes harden interpretation into dogma. The problem is not myth itself, but myth that is no longer examined. Once a story is defended against questioning, it ceases to be wisdom and becomes ornament.

From a religious sense the best way to read the Magi (this Christmas) is to ask what it reveals about us. Are we anxiously hanging on stories that don’t make sense? Or are we willing, like the Magi, to follow signs beyond our borders, accept disruption, and return home changed?

The story of the Three Kings holds a curious place in today’s commercially driven Christmas narrative. The image of three rich and powerful dudes paying homage in a humble stable resonates neatly with a season that likes its glitter and drama. Yet there is a quieter theological irony at play. The Bible records no date for the birth of Christ—a telling omission that suggests it was never intended to be marked or celebrated as an annual event. More striking still is the absence of any such detail in the Gospel of Luke. Given that Luke is believed to have drawn much of his account from Mary herself, this silence lends weight to the idea that the emphasis was never meant to rest on the birthday, but on the life and message that followed.

Inspired Word of God

The story of the Magi is neither history in the modern, documentary sense nor fiction in any trivial way. In that respect, the Bible is not a scientifically proven history book; it is, as Christians believe, the inspired Word of God. The account of the Magi, then, is best read as the courage required to recognise meaning beyond familiar boundaries.

In an age saturated with noise and uncertainty, that may be precisely why the story must command our attention.