By Tyron Devotta

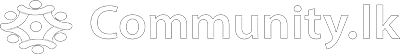

The sight of some evangelical Christians rushing to support Israel’s war in Gaza is deeply troubling. It is one thing for nations to pursue foreign policy or for individuals to hold political opinions — that is their right. But it is another matter entirely when Christians frame war and destruction as God’s will, quoting verses from Scripture to legitimize what amounts to massacre. That is not faithfulness to Christ; it is a dangerous distortion of His words.

The question I ask, as a Christian, is simple: what would Jesus have done?

When Jesus was dragged before Pilate and asked if He was the king of the Jews, His reply was striking: “My kingdom is not of this world” (John 18:36). This is not a casual remark but a profound theological declaration. Jesus was saying plainly that His mission had nothing to do with earthly kingdoms, wars, or nationalist struggles. And he was not the king of Israel. His kingdom was of a different order altogether. And that is the warning for us today: if we attempt to tie Christianity to political or military power, we betray its very essence. To justify war in the name of Christ is to misunderstand Him. To sanctify violence as part of some heavenly plan is to ignore His own words.

Jesus also told us what the heart of faith is. When asked about the greatest commandment, He responded: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: Love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments hang all the Law and the Prophets” (Matthew 22:37–40). When pressed to define “neighbor,” He gave the Parable of the Good Samaritan. A beaten man, ignored by religious leaders, is finally helped by a Samaritan — the outsider, the enemy (for those who do not know the Jews and the Samaritans were enemies). Jesus concluded: “Go and do likewise.” A neighbor, then, is not defined by kinship or religion but by mercy. To love your neighbor is to show compassion to anyone in need, even an enemy.

This is why support for violence in Gaza cannot be squared with the Gospel. Children, families, and entire communities in suffering are not abstract “others.” They are our neighbors. To bless their destruction is to turn our backs on the very commandment that sums up the Christian life. Our citizenship, as Paul reminds us in Philippians, is in heaven. We are not of this world, just as Christ is not of this world. And we are not called to love the things of this world — its pride, its lust for power, its politics of violence. Christianity is not about drawing borders or sanctioning wars. It is about embodying the kingdom of God here and now — through mercy, compassion, and love.

To misuse verses from Daniel, Ezekiel, or Revelation as justification for modern bloodshed is to repeat the very mistake Jesus corrected. The Pharisees expected a kingdom of power and armies. Jesus gave them a kingdom of love and sacrifice. By endorsing war, Christians risk aligning not with Christ, but with the worldly empires He rejected.

Jesus’ words before Pilate remain decisive: “My kingdom is not of this world.” That means no Christian can ever claim war as part of God’s will. No Christian can sanctify violence as a heavenly cause. To do so is to go directly against the greatest commandment — to love God and to love our neighbor. And if Gaza’s people — wounded, starving, displaced — are not our neighbors, then who is?

For Christians, the choice is stark. Either we follow the Christ of peace and compassion, or we twist His words to bless the very violence He condemned. There is no middle ground.

Footnote

In the Old Testament, Israel is described as God’s “chosen people” (Deuteronomy 7:6, Isaiah 41:8–9). This was not because of superiority but because God chose Abraham’s descendants to reveal Himself to the world. The covenant was conditional: Israel had to obey God’s commandments and walk in His ways. The land promise (Canaan) was tied to faithfulness. When they disobeyed, they were warned of exile (e.g., Deuteronomy 28).

In the New Testament, Jesus redefines chosenness. When asked if He was the King of the Jews, He said, “My kingdom is not of this world” (John 18:36). The Apostle Paul explains that the true descendants of Abraham are those who live by faith, not bloodline alone (Romans 9:6–8; Galatians 3:7, 29). This shifts the covenant from an ethnic nation to a spiritual family including Jews and Gentiles.

Thus, many Christians interpret that the “chosen people” are no longer an earthly nation but all who follow Christ.

The present State of Israel (founded in 1948) is a political nation, not a theocratic continuation of ancient Israel. Some evangelicals see it as a fulfillment of end-time prophecies (drawing from Ezekiel, Daniel, Revelation). Others argue these prophecies are symbolic or already fulfilled in Christ, and warn against equating a modern state with God’s eternal covenant.

Jesus emphasized the Greatest Commandment: to love God and love one’s neighbor (Matthew 22:37–40). He never sanctioned war or ethnic supremacy as part of God’s Kingdom. Therefore, many Christian theologians argue that supporting or opposing modern Israel should be guided by justice, mercy, and love—not by assuming divine favoritism for one nation in today’s politics.

Biblically, ancient Israel was chosen to reveal God, but in Christ, “chosenness” extends to all believers, Jew and Gentile. The present-day state of Israel is not automatically identical with the Biblical covenant people. For Christians, the focus should be on Christ’s teachings—justice, peace, and love—rather than nationalism.