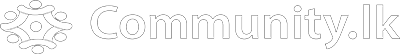

By Tyron Devotta

A Country of Four Generations, Not One Market

Sri Lanka is frequently discussed as if it were a single consumer market moving in one direction. That assumption is comforting. It is also wrong. This country is not one market. It is four distinct generations sharing one economy. Nearly half the population is under the age of 45. Gen Z and Millennials together represent the most digitally fluent, platform-native segment the country has ever produced. At the same time, Gen X and Boomers still control a substantial share of assets, savings, property, and household authority. Unlike many nations where one age group dominates demand and policy direction, Sri Lanka sits in a rare demographic balance. No single generation defines it. That balance makes economic transitions more complex and more politically sensitive.

It Was Never Really About Price

Nowhere is this generational tension more visible than in the debate surrounding platform-based mobility services such as PickMe. The public conversation often reduces the issue to pricing. Critics argue that digital platforms are driving down fares and undermining traditional taxi operators. But this framing misses the deeper shift taking place. The real transformation is not about lower prices. It is about the removal of opacity. For decades, segments of the transport sector functioned on negotiated discretion. Transparency was limited. Record-keeping was minimal. Tax capture was inconsistent. Digital platforms altered that structure. They introduced visible pricing, trip histories, ratings, digital payments, and algorithm-based dispatch systems. Whether one supports them or not, they replaced negotiation with standardization. In a discretionary economy, opacity can be an advantage. In a digitized economy, discipline becomes the currency.

Different Ages, One Shared Expectation

This is the tension we are witnessing. Younger generations, raised in a world of mobile banking, QR codes, food delivery apps, and real-time tracking, tend to view transparency as default. They are not seeking negotiation; they are seeking predictability. For them, the ability to see a fare before a journey begins is not a luxury, it is baseline functionality. Gen X is looking for balancing work and family responsibilities, values reliability and safety. A platform that allows a spouse or child to be tracked in real time provides reassurance that traditional systems did not easily offer. Boomers may not be as digitally fluent, but increasingly they are indirect beneficiaries of platforms booked by younger family members. Their concern is less about the app interface and more about security and accountability. These generational expectations are not identical, but they converge around one idea: predictability.

The Wrong Question About Fares

The debate about fare equalization must therefore be understood within a broader economic framework. When discussions arise about standardizing per-kilometer rates across all operators, the assumption is that raising platform fares would restore balance. Yet this approach focuses narrowly on nominal pricing rather than total economic activity. The more meaningful question is not what the correct fare per kilometer should be. It is what structure maximizes overall mobility, tax visibility, and economic throughput. If fares rise artificially, commuter costs increase. Ride volume may fall. Informal cash transactions could regain ground. Tax capture becomes harder to monitor. Tourism affordability is affected. In contrast, a high-volume, digitally traceable mobility ecosystem expands the formal tax base even if individual margins are moderate. For a country working through fiscal reform and revenue consolidation, that distinction matters.

More Than an App: A Formalization Tool

This is where PickMe's positioning becomes strategically important. If the company frames itself solely as a low-cost alternative, it risks reinforcing the narrative that it is competing only on price. But its broader role is more consequential. It functions as a formalization mechanism within a historically informal segment of the economy. It digitizes transactions. It standardizes earnings records. It increases transparency. It generates data that can inform transport planning and fiscal monitoring. In that light, the platform is less a disruptor of tradition and more an infrastructure layer within modernization.

Bringing Everyone Along

Yet modernization in Sri Lanka cannot afford to be generationally exclusive. Resistance often intensifies when change appears to favor one age group over another. The solution is not to marginalize older drivers or frame digital transition as a youth-only movement. It is to facilitate adaptation through simplified interfaces, language accessibility, and structured onboarding for those willing to transition. Sri Lanka's demographic composition ensures that reform must be careful but cannot be reversed. Nearly half the country is future-facing and digitally oriented. At the same time, significant economic influence remains with those who built their livelihoods in a different system.

Designing for the Next Economy

What we are witnessing through the transport debate is not merely a commercial disagreement. It is the friction point between negotiated discretion and algorithmic discipline, between cash-based opacity and digitally recorded transparency. Sri Lanka's generational balance makes this friction more visible than in countries where demographic dominance smooths transitions. No single age group can impose its worldview unilaterally. Policy must navigate across them. The question therefore extends beyond one platform or one fare structure. It becomes a broader national inquiry: are we designing economic frameworks for nostalgia, or for the generation that will define demand over the next two decades? Sri Lanka is not one consumer market. It is four generations negotiating a shared economic evolution. How platforms like PickMe communicate their role, and how the State chooses to manage this situation, will signal whether the country leans toward a more formalized, transparent system or reverts to fragmented, discretionary patterns. The outcome will shape not only the future of mobility, but the structure of Sri Lanka's next economic chapter.

This article draws on demographic research and population analysis conducted by Sajini Jayawardene, examining Sri Lanka’s generational distribution and its implications for business, investment, and market strategy. The data highlights the country’s uniquely balanced age structure across Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, and Baby Boomers, underscoring the strategic importance of generational segmentation in understanding consumer behaviour, digital adoption, media consumption, and purchasing decision-making patterns.

The analysis integrates national population statistics with digital penetration data, including internet and social media usage across major platforms such as YouTube, TikTok, and LinkedIn. It aims to provide policymakers, investors, marketers, and business leaders with a generational lens through which Sri Lanka’s evolving consumer economy can be better understood.

By reframing Sri Lanka not as a single consumer market but as four distinct generational cohorts operating within one shared economy, the research encourages more precise, data-driven approaches to product positioning, communication strategy, and long-term market planning.